Clive Trebilcock (1942 – 2004)

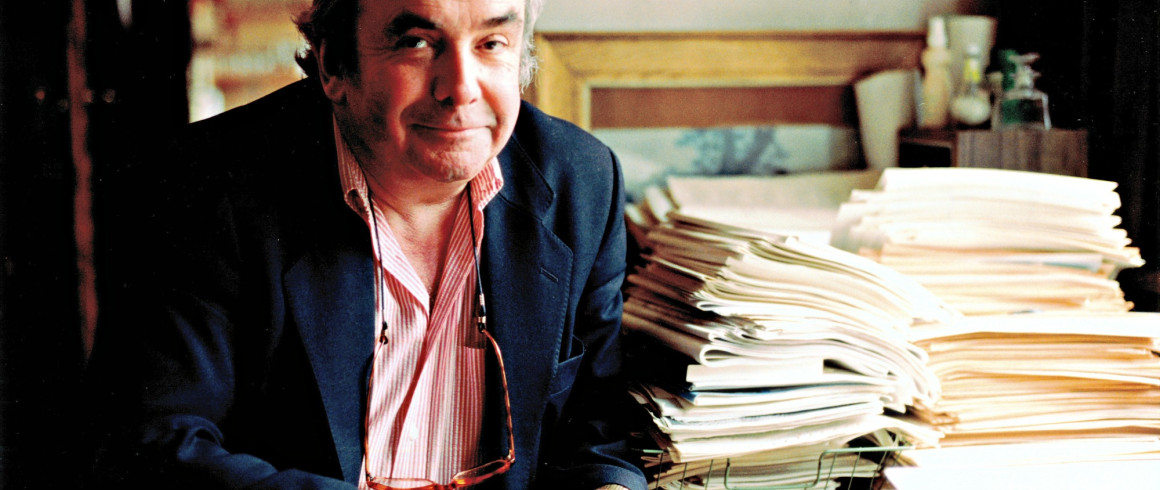

[caption id="attachment_15186" align="alignleft" width="300"] Photo by Tony Jedrej, Spring 1998[/caption]

Photo by Tony Jedrej, Spring 1998[/caption]

Saturday 12 July marks the 10th anniversary of the death of Clive Trebilcock (1942-2004, Fellow 1965-2004). A much respected Fellow of Pembroke, Clive's memory lives on among the hundreds of pupils and friends among the alumni, Fellowship and staff at the College.

Clive's work continues to live on not only through the current academic success of the College, a thriving Corporate Partnership Programme and International Programmes, but also via the Newton Trebilcock Fellowship, which was funded thanks to the generosity of Clive's friends and former students. The Fellowship is currently held by Social Anthropologist, Dr Chloe Nahum-Claudel.

Clive Trebilcock

by Neil McKendrick, Master of Gonville & Caius (1996-2005)

Clive Trebilcock’s sudden death, from an inoperable brain tumour at the untimely age of 61, will come as a shock to all of those who had witnessed his energetic, hyper-efficient and vigorous pursuit of a multi-faceted career.

Given the dazzling start to his academic life and his very obvious talents, a Cambridge Readership might seem a less than adequate return. And so it was. His achievements amounted to very much more than that. I personally rated him as one of the ablest students that I taught and since my pupils include some forty-four Oxbridge Research Fellows and some twenty-seven Professors that is no small accolade.

He came up to Caius in 1961 and was one of a glittering generation of Caius historians. Some, such as Quentin Skinner, who became Regius Professor of History at Cambridge, and Norman Stone, who was elected to the Chair in Modern History at Oxford, may have achieved higher public status and acclaim than Trebilcock but none achieved such all round success in so many areas of a collegiate university.

Trebilcock was born in October 1942 in Plymouth. His father was a company director and his mother was sufficiently active in the civic virtues to be awarded an MBE for her work, and he inherited much from both parents. He was far more interested than most academics in business yet was so imbued with the value of public service that he served his college in almost every college post. He was in turn Research Fellow, Official Fellow, College Lecturer, Director of Studies, Tutor, Librarian, Senior Tutor, Buildings Bursar, Chairman of the Development Programme and Director for International Programmes. In all of these areas he proved to be enviably successful. Pembroke’s Historians, Pembroke’s buildings, Pembroke’s Library and Pembroke’s position in the Baxter Tables of Tripos Results all showed the clear and beneficial imprint of his energetic insistence on high standards.

As did Pembroke food. Very characteristically of a man who both loved the good things of life and loved to take executive decisions, he fought for the appointment of an executive chef and in doing so transformed the quality of food in Pembroke during the last five years. Even those who were never comfortable with his decisive, business-like style and his CEO-manner, have conceded to me how effective and successful he could be in getting things done.

He was also an indefatigable Fund Raiser for his College and turned Pembroke International Programmes (an international language school which built heavily on his Japanese connections) into an integral and substantial part of Pembroke’s yearly income. Raising money for one’s college rarely seems to win either public recognition or private praise. It is certainly not an automatic route to promotion, but any sensible Master would be thrilled to have someone of Clive Trebilcock’s proven skills in this increasingly essential area of college life. It was, perhaps, no accident that when I asked the Dean of Pembroke “Who was Clive closest to in College?” he replied “Probably Howard Raingold, our aptly named Development Director”.

Success over such a wide area would have surprised no one who came across the undergraduate Trebilcock. His all-round talents were immediately self-evident when he first came up to Caius as an award winner from Plymouth College. He had already achieved his wings as a pilot of jet planes, and his career was to go from success to success at Caius. The entrance Exhibitioner became in turn a Minor Scholar, a Major Scholar and the Schuldham Plate winner as the College successively rewarded a double First in History who was awarded a starred First in Part I and came top of the University in Part II. The Schuldham Plate is awarded to the best graduand of the year chosen from all subjects, and given this accolade it was no surprise when a Studentship at Caius was rapidly followed by a Research Fellowship at Pembroke.

To achieve a Cambridge Fellowship at the age of twenty-two, an Assistant Lectureship at the age of twenty-four and a full University Lectureship at the age of twenty-six gives some indication of his meteoric early career. He always modestly attributed these rapid advances to extremely hard work, and was quick to reply, to anyone who suggested that he was very lucky to enjoy such precocious success, that he found that, like the golfer Gary Player, the harder he worked the luckier he became!

He privately and rather shame-facedly admitted that some of the undergraduate stories of his legendary hours of work were not entirely justified. Many of his contemporaries at Harvey Court who toiled on into the night to try to match his stamina would have slept more easily and for longer if they had known that the lights, which blazed all night from his rooms and with which they tried to compete, were the result not of his working through the night but the result of his fear of the dark. Characteristically he accompanied this admission with a list of the great men in history who shared these fears.

His very real commitment to the work ethic did, however, allow him to make a prodigious contribution to his college and his faculty. His fabled efficiency allowed him to carry a huge burden of teaching, administration and research. His magnum opus was his majestic study of Phoenix Assurance and the Development of Britsh Insurance from 1782 to 1870 and Phoenix Assurance: The Era of the Insurance Giants, 1870-1984. These two huge, densely researched and well-received volumes amounted to some nineteen hundred pages. In most universities they would alone have earned him the professorship he clearly deserved. Other substantial publications included The Industrialisation of the Continental Powers, 1789-1914, The Vickers Brothers: Armament and Enterprise, 1854-1914 and his contribution to Carlo Cipolla’s edited volume on The Twentieth Century in The Fontana Economic History of Europe series. He also edited (with Professor Peter Clarke) Understanding Decline: Perceptions and Realities of British Economic Performance. These, together with his work on the Japanese economy, will be his lasting legacy to the history of industrial and business enterprise that formed the central core of his academic life.

Alas business histories – like fund raising, the other thing that this short Napoleonic figure most excelled at – are not the most favoured pursuit for those in search of status in academia. Indeed it sometimes seems that they appear least to attract recognition and promotion in academic life – a truth that Trebilcock was realistic enough to accept. As he once wryly put it to me – “Well at least there are consolations - writing commissioned business histories is a better paid activity than most of the things we academics do!” I suspect that, in saying this, he may well have hit on one of the reasons why such innocent activities are so ill recognised and so inadequately rewarded with the usual academic gongs.

The gratitude of his many pupils who quickly recognised his rare qualities as a teacher came much more readily. They realised that his insistence that they should attempt to maximise their abilities was matched by his own insistence that he himself maintained the highest standards of professional expertise in his teaching.

His premature death has prevented him from achieving all that he desired and deserved. The two things that he was recently in the running for – a Cambridge Professorship and a Cambridge Mastership – might, of course, have continued to elude him. Not everyone gets what they deserve and his combative nature inevitably made some enemies. It is difficult to give forty years of an active, enterprising and ambitious life to a Cambridge college and to the Cambridge History Faculty without acquiring some battle scars on the way. Trebilcock was never a natural subordinate. He was at his best when he was in charge, as he was in running Pembroke International Programmes.

It has to be admitted that his awareness of his own abilities often made him impatient with the shortcomings he perceived in others. He was not always good at disguising this impatience. He liked things to be done efficiently and he liked things to be done fast – sometimes too fast for the authorities. As with his dashing driving which was (more than once) too dashing for the police authorities, so his schemes for collegiate change were sometimes too challenging and too soon for some of his colleagues.

It has to be admitted, too, that he was not always the most tactful of men. Soon after his first marriage, which lasted for twenty-two years and produced two daughters of whom he was very proud, he was regularly overheard introducing his young bride as “the first Mrs Trebilcock”. This jocular remark proved to be as accurate as it was prescient, and his second wife nursed him with saintly devotion through his final illness.

Both his wives survive him, as do his two daughters.

2004 PCCS Annual Gazette, pp. 153-156