“Mountainish Inhumanity”: the Pembroke Refugee Crisis Seminar

The second Pembroke Refugee Crisis Seminar took place on Friday 19th February and was chaired by the Dean, Dr James Gardom. Speaking on the topic of the continuing refugee crisis in Europe were Sir Roger Tomkys, Lord Chris Smith (1969) and Dr John Jungclaussen.

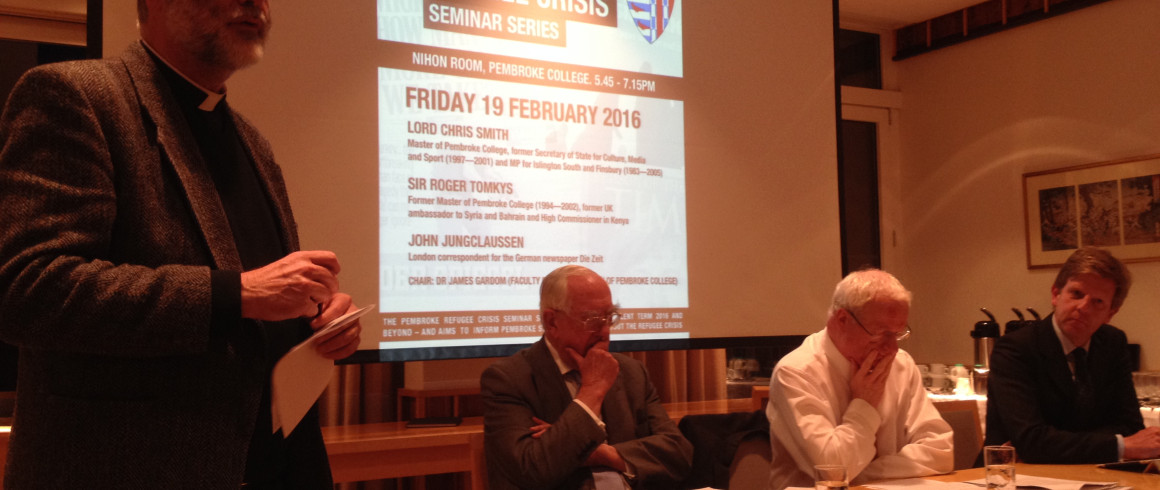

[caption id="attachment_23576" align="alignright" width="300"] L-R: Dr Gardom, Sir Roger Tomkys, Lord Chris Smith, and Dr John Jungclaussen[/caption]

L-R: Dr Gardom, Sir Roger Tomkys, Lord Chris Smith, and Dr John Jungclaussen[/caption]

Sir Roger Tomkys was Master of Pembroke from 1992 until 2004. During his long career as a diplomat, he also served as British Ambassador to Bahrain (1981–84) and Syria (1984–86) and retains his interest in the subject of Middle Eastern politics. He opened by discussing the Syrian government’s “reputation for brutality” among the Arab world, citing the 1982 Muslim Brotherhood uprising which was put down by a media blackout and the killing of an unknown number of people. The ‘Arab Spring’ occasioned another, less brutal response from the government, and by 2011 Syria was facing armed insurrection. Sir Roger also offered his opinion on the West’s “horrible track record on regime change and its outcomes”, stating that the West too often works for its own interests and not out of concern for the people living in these areas. He described the problems in Syria as being in reality a “proxy fight over power” between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Speaking of the influence of the media on public opinion in the UK, Sir Roger commented that the press has so far been hugely misleading on the issue of Syria, both from an opposition and a government perspective, and that there has been very little objective reporting.

Lord Chris Smith, the current Master of Pembroke and formerly an MP and Chair of the Environment Agency, provided a political point of view to follow Sir Roger’s diplomatic perspective. The crisis currently facing UK politicians is a question of how to respond to the refugee situation. There are currently around 19.5 million refugees, half of whom are children, seeking safer lives in Europe and other countries. The “frontline states” – Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey – are now home to crowded refugee camps, along with the so-called ‘Jungle Camp’ in Calais. Lord Smith outlined the two main approaches to the problem. Firstly, we have the ‘moral case’, which he explained by quoting a passage from The Book of Thomas More, a play partially written by Shakespeare:

‘Would you be pleased

To find a nation of such barbarous temper,

That, breaking out in hideous violence,

Would not afford you an abode on earth,

Whet their detested knives against your throats,

Spurn you like dogs, and like as if that God

Owed not nor made not you, nor that the claimants

Were not all appropriate to your comforts,

But chartered unto them, what would you think

To be thus used? this is the strangers case;

And this your mountainish inhumanity.’

There is also the ‘practical case’, since the refugees approaching Europe are often highly skilled and educated people who could bring significant benefits to their adoptive countries. The political dilemma centres around public opinion, fuelled by the “cheaply populist media” and expressing fear of strangers and of austerity. What should the political strategy be to solve the current problems? Most importantly, Lord Smith suggested, we should strive to end the conflict within Syria; we should fund the frontline states to provide emergency shelter; we should instigate a cross-European agreement to take in certain numbers of refugees per country, and provide more support to countries such as Greece and Italy which have already taken in large numbers of people; the rest of the world should be encouraged to act (the USA, for example, has so far done almost nothing to help); Britain should agree to accept more than the 20,000 refugees over five years which is our current target; a refugee processing unit should be set up in Calais; and there should be immediate provision for unaccompanied children, as there was at the beginning of the Second World War. While these options could go some way towards tackling the issue, Lord Smith concluded, we must bear in mind that “this is a problem that doesn’t have any perfect solution”.

Dr John Jungclaussen is the London correspondent for the German newspaper Die Zeit. He discussed the current crisis in the context of Germany’s historical and cultural background, explaining that 2015 was an “incredible year” for Germany: refugees were welcomed in large numbers in August, and in December the Chancellor, Angela Merkel, was named Time magazine’s Person of the Year. Then, however, the New Year’s Eve attacks on women in Cologne were reported, and it was as if Germany had become “a different country” by January: Merkel had gone from being the architect of ‘humanity’s finest hour’ to being accused of ‘destroying European society’. Dr Jungclaussen liked this to the German response in 1989 to the fall of the Berlin Wall, which he described as mingled “incredulity and elation”, followed by an intense fear and uncertainty as to how Germany was to deal with this development. The politicians of the time did deal with it, but the question now is whether Germany’s response to the refugee situation will prove sustainable. Dr Jungclaussen describes the current migrant situation as an “event”, rather than a crisis, on the grounds that a crisis involves reversing a threat to the status quo, whereas the migrant situation is much bigger and will change Europe forever. Recent surveys show that 70% of Germans are still as committed to helping refugees as they were in August 2015, but politicians now face the challenge of dealing with the bigger situation.